THE SOUND AFTER

JOHN CIMINELLO

|

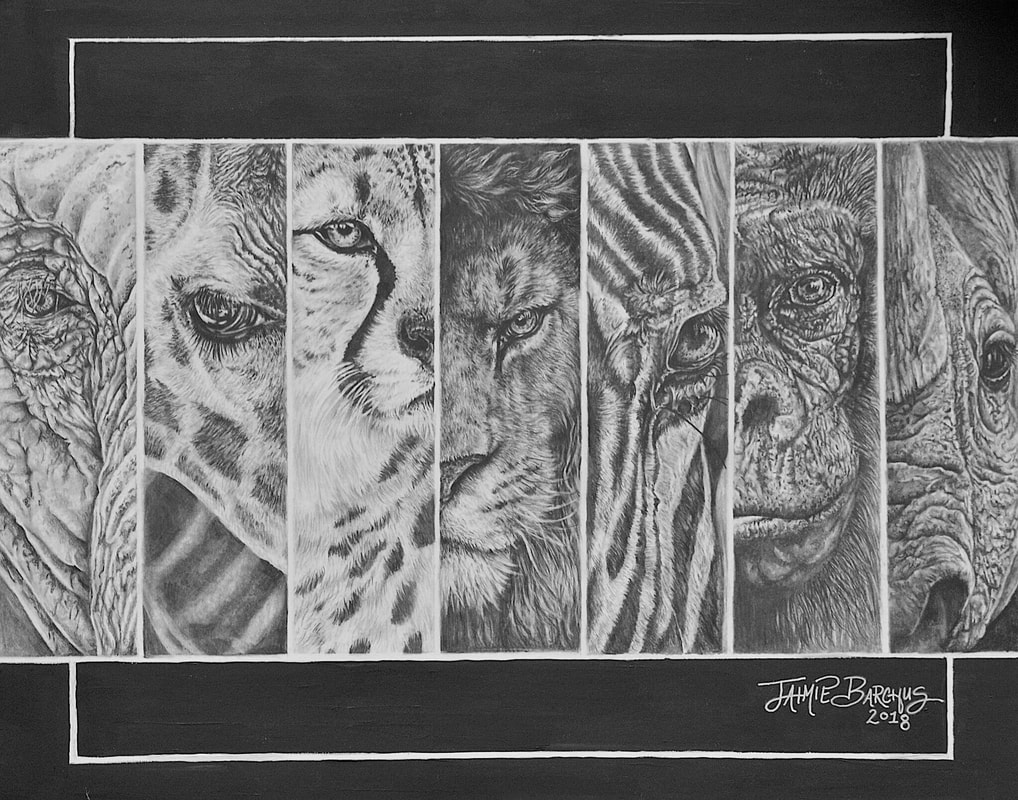

SEE ME, SAVE ME

|

The Salal Review is published annually by the students of Lower Columbia College enrolled in Arts Magazine Publication. Copyright @2024 The Salal Review and the individual contributors. No portion of the publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form without the express permission of the individual contributor.

The Salal Review is a non-profit publication for the sole benefit of the community and is not available for purchase.

LCC is an AA/EEO employer - lowercolumbia.edu/aa-eeo

The Salal Review is a non-profit publication for the sole benefit of the community and is not available for purchase.

LCC is an AA/EEO employer - lowercolumbia.edu/aa-eeo

Proudly powered by Weebly