THE SALAL REVIEW is the annual, award-winning arts magazine of Lower Columbia College, created by the students enrolled in Arts Magazine Publication, along with paid student editors and graphic designers. Each academic year, new teams of students work together to anonymously review literary, visual, and performance art submissions from diverse students, staff, faculty, and community members of all ages with a connection to the Lower Columbia region.

|

Thank you to everyone who joined us for this year's launch of The Salal Review, Volume 24. If you missed us, printed copies are free and available for pick up throughout campus. You may also find copies tucked away in the creative corners of our surrounding community...

We are so pleased to introduce, for the first time ever, a publication of Performance Art (online only). Enjoy music, spoken word poetry, and video art! For a digital reading experience of our literary and visual art from Volume 24, as well, click on the "read" button below. We also encourage you to consider submitting your work for next year's volume; submissions are open here!

Wondering how to get involved? Contact Amber Lemiere, Faculty Advisor, at [email protected]

|

About The Salal Review |

The Salal Review, Lower Columbia College's award-winning, annual literary and visual arts magazine, showcases an inspired collection of created works by students, staff, faculty, and community members who have a connection to the Lower Columbia region.

Our editorial team is comprised of student editors and faculty advisors who curate and publish each year's volume during the academic year. Students must register for Arts Magazine Publication (Humanities 124, 125, and/or 126) during fall, winter, and/or spring quarters. These courses satisfy the humanities requirements for many degrees and certificates. In 2008, 2009, 2013, and 2017 The Salal Review won the Washington Community College Humanities Association Literary and Arts Magazine Award. |

To learn more about our magazine's history and evolution over the past twenty plus years, watch Joseph Green and Amber Lemiere (former advisors) present about The Salal Review for Community Conversations, Winter 2020.

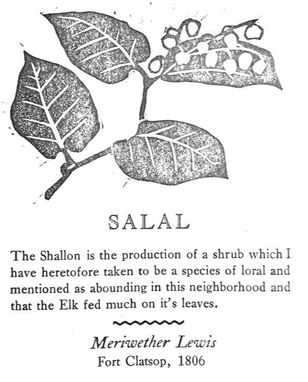

Why Salal?"If the Green Man and the Great Goddess Had Skin and Bones, They Would be Named Salal"

by Robert Michael Pyle In calling itself Salal, this journal takes the name of the very plant that binds its region together.

When I consider salal, I think of a shiny evergreen shrub that, as much as any other organism, shouts "Washington" as it spurts from the spring-warmed earth. Trying to take its measure once before, in Wintergreen, I wrote of "endless acreage of glossy-leaved salal. Impenetrable, salal gives the impression of one endless, interconnected plant, up and down the Northwest coast." I have not changed my opinion. Salal is a member of the Ericaceae—the Heaths—related to the red huckleberries with which it conspires to rescue clearcuts, as well as huckleberries, madrona, manzanita, kinnikinnick, pipsissewa, heathers, and rhododendrons. You can see its affinities to these in its muscular ruddy trunks, and especially in its bell-shaped flowers with stamens that slit lengthwise to release their pollen. Big-leaved salal Gaultheria shallon ranges all up and down the coast from northern California into Southeast Alaska, and inland well into the Cascade foothills. Another species with smaller, rounder leaves (western teaberry, Gaultheria ovatifolia) occurs at middle elevations, and alpine wintergreen (Gaultheria humifusa) still higher in the mountains. The habit varies from low, loose growth to ten- or twelve-foot tangles, and the tough, flexible branches withstand crushing by snow. Salal served important roles for the first Northwesterners, who gave it the name. The sticky, pulpy berries provided one of the most abundant and available fruits in their diet. Many Indian groups used salal to sweeten other foods, in a syrup, to dry or pound into a mixed-berry pemmican for travel and trading, to mix with salmon eggs, and for dipping in the prized, rancid grease they made from the smelt (eulachon oil). Few people pick the berries nowadays, compared to blackberries, but I can attest to their wonderful flavor fresh, for jellies, and in salads, pies, and purees. Natives used the young leaves to stave off hunger, and the branches for pit-fires and pot-flavoring. Florists, who value its size, natural shellac, and longevity, employ the foliage extensively. The shrub is cut commercially, along with sword ferns and cascara bark, by out-of-work loggers and others in search of a day's pay beneath the dappled canopy of the managed forest. As an ornamental shrub, salal has grown in importance ever since the visiting botanist David Douglas, of fir fame, recognized the plant's potential and introduced it to Britain in 1828. Arch-botanist Professor Arthur Kruckeberg of the University of Washington, in his classic Gardening with Native Plants of the Pacific Northwest, writes: "So much a part of the natural landscape and yet so neglected (or even rejected) as an ornamental in former years, it is consoling to see salal now come into its own. For years suburbia has extirpated this lush shrub as though it were a weed. Now it is the 'cinderella' plant of the developer and highway engineer." Those who seek to attract wildlife also love it, as both cover and food source for backyard birds. I think of particular times with salal, in particular places and many others like them. One such time and place was Open Bay on the northwest coast of Vancouver Island, visiting my former bird and mammal mentor, Professor Frank Richardson and his wife Dorothy, who made good life in a small cabin for a year while studying the bird migration in that remote locale. Dorothy conjured superb jelly from salal and wild crabapple, the first I'd tasted. And six of us wormed our way through seemingly endless tangles of salal to reach perfect, unpeopled little beaches piled with Japanese glass floats. Or farther down the island in a later March, hiking the Shipwreck Trail (now blandly called the West Coast Trail). That historic lifesaving track was carved largely through salal, which was in fact one of the main reasons for building it: survivors of wrecked ships could make it to shore, could withstand the mild climate, but died in the end, unable to negotiate the coastline to reach Port Renfrew or Barnfield because of the impenetrable miles of solid salal. Even today, in fact sometimes more so in the absence of Indian fires, salal seems to tie the headlands together up and down the coasts of Oregon, Washington, and British Columbia. I also think of salal in its hedgelike banks along the roads of the Willapa Hills, loaded with creamy pink bells that may appear in any season but especially in spring, a bonanza for emerging bees. The blooms also supply one of the main host plants for the brown elfins, small sienna butterflies tinged with chestnut and violet that flit improbably among the heaths during sunbreaks on either side of Easter. We enjoy them now here in Gray's River, and I remember long ago sitting out behind the HUB at the University of Washington, watching brown elfins' territorial behavior. Males would stake out sunny Fatsia plants along Stevens Way and lie in wait to dart out at passing females or intruding males. They brought a note of vitality to my textbook studies of natural history, sprung from caterpillars feeding on the flowers of the prolific campus patches of salal. Many other insects utilize salal: their edges are often crimped and scalloped by leafcutting grubs such as the strawberry root weevil, as if by fancy scissors, and inscribed with the loopy runes of leaf mining larvae of micro-moths. One winter, in desperation, I even attempted feeding the gargantuan lime-green, blue-and-orange tubercled serpents that grow into Polyphemus moths on salal leaves. I'd ended up with a winter generation that kept eating instead of forming cocoons, and after the last oak leaves were gone to brown litter, salal was all there was. I doubt this has ever happened in nature. The vast caterpillars ate the leathery leaves with obvious disdain, and made stunted pupae and grudging, shrunken adults come spring, but they made it through. I live daily and nightly with salal. There is a thick bed of it by our back porch, the canopy of a native plants garden. It furnishes a windbreak for the kitties, privacy from the road, protective cover for reticulated slugs and velour snails and snail-feeding beetles and such all winter long; a frost-safe tent for maidenhair fern and wood sorrel shamrocks leafing forth in fickle April; sticky fragrant florets in spring, and piquant berries for late summer snacks. Not least, it allows me to feed the cats in the nude, if I am so inclined. We citizens of the Northwest are the lucky ones to have salal all around, an evergreen gift of the wintergreen world, twining us tightly to the land. |